Maria Mateescu • Engineering Log

How to Code with Push Safety in Mind

Disclaimer: This is a post summarising a couple of different hour-long talks I have given in the past about push safety and engineering best practices. I have tried to be succinct, as well as abstract away any company specific details.

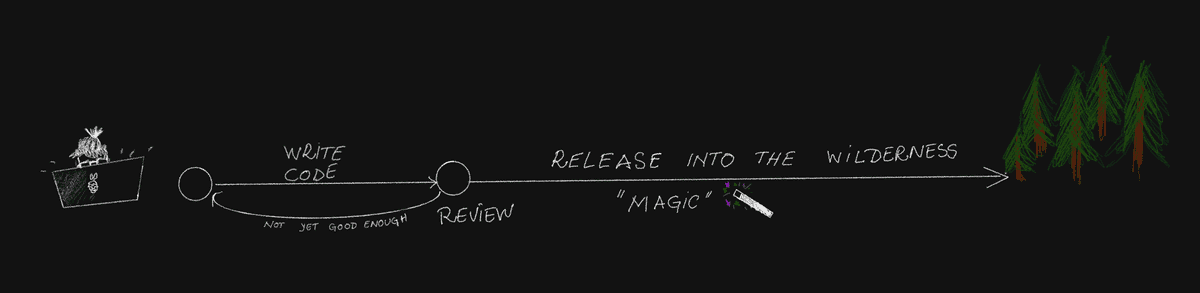

What is the push?

Here by push I refer to the process of getting the code out to the user. Basically all the magic, that when working with CI/CD pipelines tend to happen automatically from the perspective of the developer.

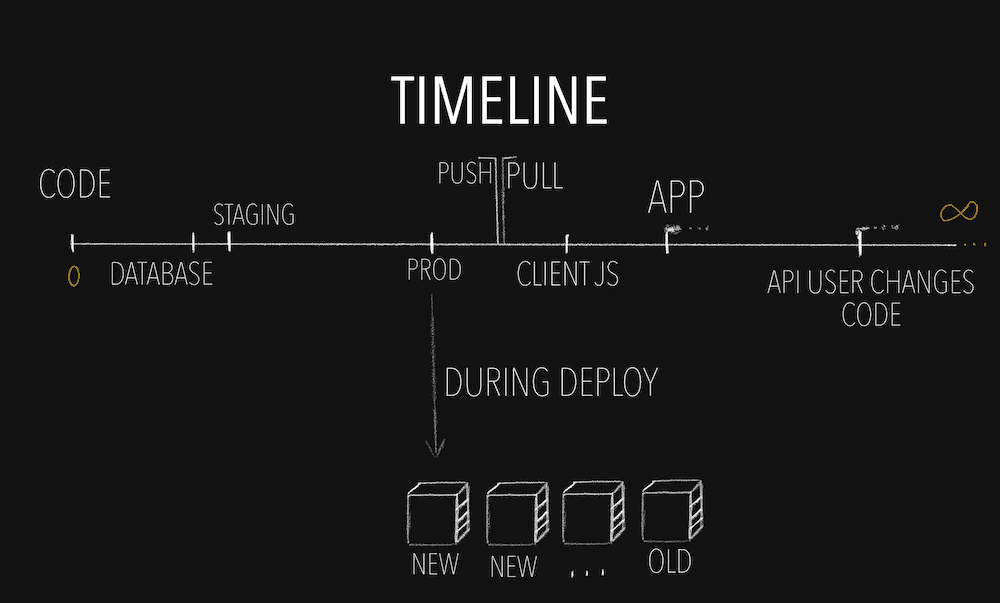

I only look at the stage after the diff/pull request has been merged in to the main branch and there is a working build. Clearly marked on the above timeline as "magic". This build is what we want to get running in production (i.e. the users get/hit it).

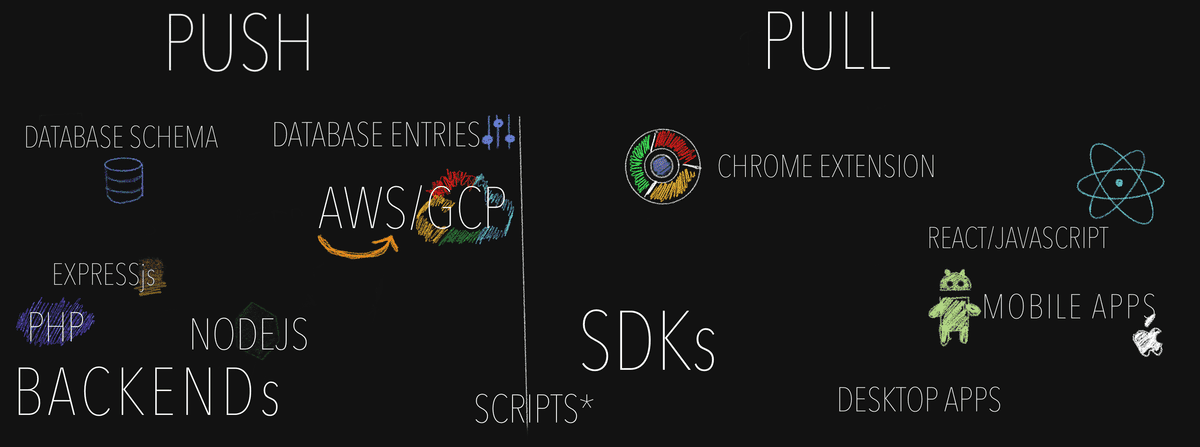

To add to the confusion of terminology, and why there is a section of what is push, there are two types of push. Push and Pull.

The push type push is the nicest. What it basically means is that we can force an update at any point we want. One way to think about it is "do we own the devices on which the code is running?", though in a world of cloud providers like AWS or GCP, own may need to be used loosely. It may give us a small fake sense of safety when we control the machines, but there are certain complications that can appear even here (the most common one I have seen is data corruption, I will talk about it later in the examples)

The pull type push is the most tricky. It refers to the code that the user decides when to update. The most obvious examples here are apps that need to be manually updated, or SDKs that need manual updating by an engineer. But another one people sometimes forget is front end JavaScript code. Browsers often cache the JavaScript for a page in order to make things faster and more reliable. (Imagine you were writing a message to a friend, two paragraphs in the release of a new frontend happens, and you loose all your progress because the JavaScript decided to update itself, and you need to start over... that would not be nice, would it?) When we are looking at Apps and SDK, depending on the users, while there are ways to block certain versions, this does not provide a good user experience. If we have a large user base, some might be in areas where internet is not as readily available, which means it is impossible for them to update their apps. So live with the knowledge that if something is mobile, there may be at least one user who will live with those changes forever, because at the end of the day we cannot force a change in something we do not control.

What is push safety?

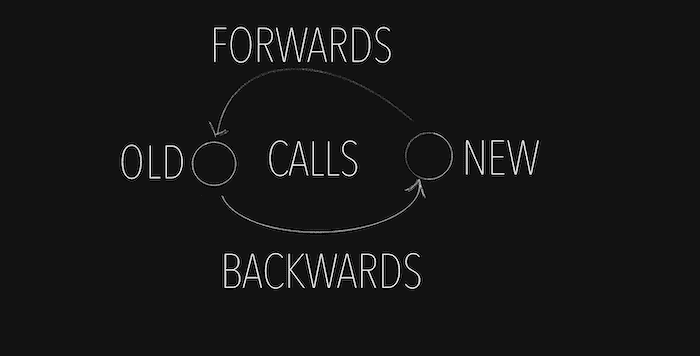

Push safety is a concept or practice that ensures we develop code in a way that does not break anything when we push new code. Basically we want to ensure that the old code is compatible with the new code (forwards compatibility) and the new code is compatible with the old code (backwards compatibility).

As old and new code can co-exist at the same time, push safety is something we need to have in mind to ensure that if new versions of the code call old versions of the code, and the other way round the code will still work.

So why do I need to care?

Well, technically you don't need to. Just look at how MMORPGs like World of Warcraft famously do software updates. There are a certain number of hours scheduled once in a while when no-one can play the game when the servers update, and then everyone is forced to download and install the latest update before they connect to the servers. They can do that. And they don't need to write code that is backwards or forwards compatible. But isn't this also a method of push safety too?

Backwards compatibility

Backwards compatibility is making sure that while there is old code that is running somewhere in the world that can interact with new code, then the new code should not break. So the new code needs to have a way to handle it when it's called by old code. Mind you, this doesn't need to be forever.1 This compatibility needs to be maintained for the duration where both can coexist which can be minutes, days, or forever depending on what type of push we are talking about. For that we need to make sure the old code does not exist anywhere in the world. There is no device that is holding on to the old ways, there are no machines running the old code, it doesn't exist in any way shape or form. In order to do that we probably need to look at the timeline of that code.

Notice that with the PULL type pushes, we do not control when the old code stops existing. We can sometimes make educated guesses (most browsers only cache the JavaScript for a few days), but often, in order to be sure that we absolutely have no more old code out there, we will need to add some good ol' trusted logging, where we keep track of the version running, and when we see the old one disappear, then we can stop caring about the backwards compatibility.

Forwards compatibility

This one is one even I struggle to wrap my head around sometimes, still, even after working in multiple different release engineering teams. This is when new code calls old code. From the name itself "forwards", it gives you the hint that the old code is the one that needs to gracefully handle when it's being called. But you may ask "How does this make sense? The old code doesn't know what the new code is, if it did, we would have written the new code in the first place." Yes... and no. There are certain operations that however you write the code that will never be backwards compatible, regardless of how careful you are when changing them. Forwards compatibility is mostly trying to avoid those. I have seen it more often discussed in the context of engineering best practices than in a push safety context (these are not unrelated), and as a whole it is making your code more resilient to change. One example of better engineering practice that is backed by forwards compatibility is avoiding required fields in thrift structures or protobuffers. Forwards compatibility can rarely be gauged by looking at two different code versions, because if the next code version exists it's usually more of a question of backwards compatibility. So in code review or when coding in general, forwards compatibility is often a question of "How much of a nightmare will I have if I need to change this in the future?".

There is however one additional situation where forwards compatibility becomes an interesting question, and that is when forwards compatibility becomes backwards compatibility. This actually to me is the most important. There are situations, imagine major outages, security exploits, etc. where in order to resolve an issue one needs to revert back to an old state. In my opinion, we should write code that always allows us to do that, because the old state should be "known good". When this revert happens, the old code is technically the new code in the discussion. If the code was forwards compatible, then it means the revert is backwards compatible, thus safe to roll back. If we roll back we can quickly un-break the code for the users, while also calmly being able to fix the problem after.

How do things break if backwards compatibility is not followed?

The interesting thing about backwards compatibility breakages is that when they break, they do tend to resolve themselves, eventually, as the new code replaces the old everywhere. Depending on the length of your release process that could however be month, years or maybe never (if we look at usage of mobile apps in developing areas). They are fairly easily distinguishable as they tend to start with the push.

So how can I unbreak a push safety problem?

Sometimes one gets lucky and while the code is not backwards compatible, it might be forwards compatible, and we can just revert the change, and then rewrite it in one or more changes that are backwards compatible. However, that is not always the case, reverting the change could actually make things worse (one example could be data corruption). Sometimes, it is possible to force updates even in PULL type pushes, and in some cases the breakage is bad enough to justify the bad user experience to fix it. Ultimately it's not the easiest one to fix, so it's one best avoided if possible.

My favourite of all methods however, because it stops a lot of other problems too is to protect new features and changes under feature flags. This would allow to slowly roll out changes in a controlled way, and this in itself encourages more awareness of push safety, but also safer development. If something breaks, we can just turn it off, easy. And this isn't just for push related issues. It is often the fastest way to unbreak something, and is the preferred method of resolving issues. And consider it even if you do not care about slow roll-outs, or they may even lead to problems if they are slowly rolled out. The feature flag could just be an on or off.

How does one do push safety?

Having gone through the conceptual discussion I think it is worth going through some more practical (non-exhaustive) examples. There's a lot of things that can fail, some are obvious, some, even with my years working on this, are just very hidden. There are always rules of thumb one can follow to prevent this from happening, but they're not always easy. And even then things can slip through.

Database changes

One classic place where push safety issues happen is when we need to do database changes. Database changes themselves also don't exist in a vacuum. There's no point in holding the data is we don't have code that uses it2. Any change to a data model has a potential to not be backwards or forwards compatible. This being a very common sort of thing we have ways to deal with the most common issues.

- Dropping a table/column: Ever drop a table, or a column, and it was still in use? Let me tell you it's not fun. Even if it was completely empty, full of nulls. Remove all references to the table/column first and only then, after a while and no-one is using it anymore, drop it. Warning: logging may be required.

- Adding a column: Arguably the safest database change out there... unless you make it mandatory... in which case chaos may ensue. Just... don't make it required?

- Renaming a column: It would come as no surprise that if you renamed a column there would be quite a lot of confusion about where to go to get the data. Obviously you can't just rename it, because that is deleting a column already in use. So we create a new one, and direct people to the new one. But then... which one is the source of truth? Pushes don't magically happen all at once, they take a while for each machine to update. Not too many at a time, otherwise your service goes down. So during that time you have people working on the old column, and some on the new one... In this case in particular the steps tend to be: create a new column; duplicate the data across both columns and have the code write to both at the same time, while still reading from the old one; start reading from the new one; when the old one stops being read from, stop writing into the old one; when the old one stops being written to, finally drop the old column. A long process, right?

During push issues

This is one of those "But it worked on my machine" type of problems. It could be that there's only one service, and only one backend that has been touched, and still push safety issues come up. This often happens when an essential behaviours change significantly. As the push is not instantaneous, as the service is likely running on multiple servers for reliability, the two behaviours will run in parallel. The problem here comes that a user is not necessarily pinned to a specific server, and while the change may be fine if the user only hit the new or old behaviour, when they hit both issues may occur. The most common ones I've seen in these cases is data corruption. These are some of the trickiest push safety issues I've seen, both to spot and to fix.

If you suspect however this to be the case a feature flag is an excellent thing to have. You roll everything out with the feature flag and your code changes turned off, and then when everything has released everywhere, you can turn the flag on. Then if everything is ok, go clean up all the old code.

Common front-end and back-end libraries

This is something that I've seen happen a lot where the language is the same across backend and frontend(JavaScript/Typescript). There are certain operations what we may do across front end and back end at times. So as good little engineers, who dislike duplication, we create a common shared library that both frontend and backend use. Amazing... only that if we change anything in those libraries, the front end and back end will have a period when they will have different results. If for example you're changing the validators, you'll have a frontend that is very confused as to why their seemingly correct input failed.

It's part of why I personally prefer having a different language between back end and front end. We can't have these common libraries in those cases. Additionally, when reviewing the code, it is easier, at a glance to tell what is frontend and what is backend code, making it easier to spot possible inconsistencies.

Frontend changes

While I am calling this example front end changes this applies to anything that uses a pull model.

Probably the most common of them all. I definitely got caught out by this a few times. Especially when I was starting out as an engineer. I even was careful about the push safety concerns when writing my code. It was deleting some functionality, if I remember correctly. I did the right thing and removed it from the front end first, waited for the push to finish. And then, as it was late, I even waited until the next day, and then released the back end. To my surprise not everyone had the new front end and things broke.

Ultimately the advice is wait until all the backends and front ends or other dependencies like scripts, etc to get to everyone after releasing the changes that break functionality. And yes, ideally you would not break functionality, but things get deprecated, decisions change... Change happens. Logging is your friend here.

How do I test this?

The insidious thing about push safety bugs is that testing them needs to be intentionally looking at push safety issues. When you run your code to test it, you're running the latest version on every single service and surface you have modified. It will test that your code will eventually work. But it won't test if it will work while it is being deployed.

The one way to test this is to figure out which code runs on which deployment schedule and then comment out individual parts that deploy on different schedules to see how your code will run. It is often nice to keep these separate code review wise, but I understand that when adding a functionality to the frontend and backend, which tends to be push safe, it is a faster not to. (especially on Github) There was a time when the exact same code was being deployed to two different services that interacted with each other, however deployed on two different schedules. Nobody caught the fact that the code needed to be the same in both for the change to work, and the second service went down completely. Fortunately it wasn't something user visible, but it still wasn't great.

So complicated... I don't want to do it

Nothing in this world is mandatory. If you don't want to care about push safety, don't. But be aware of the implications of that. If your take from this post is "I can see how this breaks things, but I don't care if they break, I'd rather implement changes fast", then this is fine by me. Because now it's an informed decision you have made. You know your users better than I do, and they may actually not care3. There are also many workarounds that don't necessarily require downtime. One is the WoW "We're doing changes" sign. Another is Google's, we'll just rebuild a new alternative from scratch4.

Push safety takes time, because it happens in stages. And you need to wait in between each one. That is why Facebook, whose motto is Move fast, has put so much effort in making their releases be every 2 hours. That way the wait is shorter. When you're at a small company with a small set of users the wait could be even shorter, which is one of the reasons big companies move a lot slower than lean startups. They can't afford to break things.

Cool, but this seems hard

It is hard. I have seen some extremely seasoned, incredibly knowledgeable engineers make push safety mistakes that did take down services. It happens. The goal here is not to prevent all issues (though that would be amazing), but to prevent them as much as possible. The bigger a system or a company gets the more cogs there are in the game, and to fully be able to prevent any and all push safety issues one would have to know how they all interact with each other. This is not always possible. However, there are best practices, some that I have highlighted above that will sure help make this a rare occurrence.

Conclusion

When there are changes there is always risk. Think of push safety as a series of best practices that help mitigate those risks. The only code that doesn't ever break is no code. So things may break sometimes, but if we follow some best practices, we will reduce how often that happens, and how quickly we can recover from it.

1 Unless you ask Microsoft. Microsoft products are legendary for how long they maintain backwards compatibility. But it comes at costs.

2 In fact it's probably a bad idea, and there's a few customer data privacy commissions you may not want to hear about it, so delete it. They won't care that you don't use it.

3 Like take this blog, for example. Do you think I spend a lot of time caring about push safety? No0. I know I write this mostly for my own benefit, and probably most of the people who read it, I have given the link to. It just wouldn't make sense for me to care if my website is down for like 20 minutes. (I think it wouldn't even matter if it was days...)

4 An attitude that lead to the famous Google comic of the choice between the two roads, one deprecated the other under construction.